Which Intrapartal Factors Can Contribute to a Postpartum Infection? Select All That Apply.

- Research article

- Open up Access

- Published:

Incidence of postpartum infection, outcomes and associated risk factors at Mbarara regional referral hospital in Uganda

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 18, Commodity number:270 (2018) Cite this article

Abstract

Groundwork

There is a paucity of contempo prospective data on the incidence of postpartum infections and associated run a risk factors in sub-Saharan Africa. Retrospective studies estimate that puerperal sepsis causes approximately ten% of maternal deaths in Africa.

Methods

Nosotros enrolled 4231 women presenting to a Ugandan regional referral infirmary for commitment or postpartum care into a prospective cohort and measured vital signs postpartum. Women developing fever (> 38.0 °C) or hypothermia (< 36.0 °C) underwent symptom questionnaire, structured concrete exam, malaria testing, claret, and urine cultures. Demographic, treatment, and mail service-discharge outcomes information were collected from delirious/hypothermic women and a random sample of 1708 normothermic women. The main upshot was in-hospital postpartum infection. Multivariable logistic regression was used to determine factors independently associated with postpartum fever/hypothermia and with confirmed infection.

Results

Overall, 4176/4231 (99%) had ≥1 temperature measured and 205/4231 (5%) were febrile or hypothermic. An additional 1708 normothermic women were randomly selected for additional information collection, for a full sample size of 1913 participants, 1730 (ninety%) of whom had complete data. The hateful age was 25 years, 214 (12%) were HIV-infected, 874 (51%) delivered by cesarean and 662 (38%) were primigravidae. Amid febrile/hypothermic participants, 174/205 (85%) underwent full clinical and microbiological evaluation for infection, and an additional 24 (12%) had a partial evaluation. Overall, 84/4231 (2%) of participants met criteria for one or more in-infirmary postpartum infections. Endometritis was the almost common, identified in 76/193 (39%) of women evaluated clinically. Twenty-five of 175 (fourteen%) participants with urinalysis and urine culture results met criteria for urinary tract infection. Bloodstream infection was diagnosed in 5/185 (iii%) participants with claret culture results. Some other 5/186 (iii%) tested positive for malaria. Cesarean delivery was independently associated with incident, in-hospital postpartum infection (aOR 3.9, 95% CI 1.5–10.3, P = 0.006), while antenatal clinic attendance was associated with reduced odds (aOR 0.iv, 95% CI 0.2–0.ix, P = 0.02). There was no difference in in-hospital maternal deaths between the febrile/hypothermic (ane, 0.v%) and normothermic groups (0, P = 0.11).

Conclusions

Amongst rural Ugandan women, postpartum infection incidence was low overall, and cesarean delivery was independently associated with postpartum infection while antenatal clinic attendance was protective.

Groundwork

Postpartum infection is a leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide. Approximately five million cases of pregnancy-related infection occur every year globally, and approximately 75,000 event in death [1, 2]. Infection incidence is higher in low-resource settings, and many infection-related maternal deaths are preventable [ane, ii]. Postpartum infections are a subset of maternal infections occurring between commitment and the 42nd day postpartum [3]. The most mutual postpartum infections include endometritis (puerperal sepsis), urinary tract infections, surgical site infections, claret stream infection and wound infections [iii, four]. In a retrospective written report from Mbarara Uganda, puerperal sepsis accounted for 31% of maternal deaths, making information technology the nigh common cause of maternal mortality at that facility [5].

Most research on postpartum infections has occurred in high resource countries, where chance factors include poor intrapartum hygiene, low socioeconomic status, primiparity, prolonged rupture of membranes, prolonged labor, and having more than than v vaginal exams intrapartum [six]. In these settings, cesarean delivery appears to be the single most important risk factor for postpartum infection [3, vi]. In low-resource settings, risk factors for postpartum infection are poorly defined and may differ from loftier-resource settings due to patient, environmental and healthcare organisation factors [1]. In improver, most published studies from low-resource settings exercise not include microbiological confirmation of infection or infectious outcomes [3].

We performed a prospective accomplice report to decide the incidence of postpartum infection among women with postpartum fever or hypothermia presenting for commitment or postpartum care at Mbarara Hospital. In addition, the study compared clinical outcomes between the fever/hypothermic group and the normothermic group, and examined risk factors associated with incident fever/hypothermia and a composite postpartum infection result.

Methods

Written report site and design

We conducted a prospective cohort written report among women admitted for commitment or postpartum care at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital (MRRH) in rural Uganda, in which a total of 4231 participants were enrolled. MRRH is both a regional referral and teaching hospital for Mbarara Academy of Science and Technology with 11,000 deliveries annually [seven, viii]. Information from the entire cohort of participants was used to determine which gamble factors were associated with developing a fever or hypothermia while hospitalized.

Enrollment and information collection

Women admitted to the maternity ward at MRRH for delivery or within 6 weeks postpartum were screened for enrollment into the study. Participants providing written informed consent were followed past research nurses who measured vital signs including heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate and oral temperature approximately every 8 h starting immediately after commitment, as previously described [7]. Participants who had not been tested for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) within the last 6 months were offered HIV testing. Women who did not understand English language or Runyankole (the local language) or were incapacitated and their side by side-of-kin declined participation were excluded from the study. Questionnaires and laboratory results were entered into a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database [9].

Sample size and planned analyses

The sample size was calculated at 3500 participants, the number of participants needed to notice a doubling of postpartum infection hazard from 5 to x%, comparing HIV-uninfected to HIV-infected women. An additional 721 participants were enrolled to examine secondary outcomes for a nested sub-study. All analyses described in this manuscript were planned a priori before cohort enrollment began.

Sample collection and microbiology

A symptom questionnaire and structured concrete examination adult by written report investigators was administered to all participants febrile to > 38.0 °C or hypothermic < 36.0 °C by a trained research nurse. Febrile and hypothermic participants were tested for malaria using the SD Bioline Malaria Ag Pf/Pan rapid diagnostic exam (RDT, Standard Diagnostics, Gyeonggi, Korea), provided a clean-catch urine sample, and had peripheral claret fatigued aseptically into Becton Dickinson (BD) BACTEC (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, United states of america) aerobic, anaerobic and mycobacterial blood culture bottles. Blood civilization bottles were processed at the Epicentre Mbarara Research Centre microbiology laboratory side by side to MRRH every bit previously described [vii].

Additional data collection

All participants who were febrile and hypothermic and a randomly selected sample of normothermic participants underwent structured interview and nautical chart review at time of hospital belch. Random selection was performed using a random number generator role in Excel, with the goal of selecting five normothermic participants for every delirious/hypothermic participant. Participants were followed upwardly by telephone at two and 6 weeks postpartum using a structured questionnaire to determine maternal and infant vital status, interval healthcare encounters and antibiotic usage. Interview tools were created by report investigators and pilot-tested prior to study start. Data from all participants were included in the final analysis, even if participants had missing data on specific variables. Gestational age was defined past participant study or nautical chart documentation of last normal menstrual period. Pregnancy losses at < 28 weeks' gestation were divers as miscarriages.

Defining postpartum infection

Postpartum endometritis (puerperal sepsis) was divers as infection of the genital tract with two or more of the following: pelvic pain, fever > 38.0 °C, aberrant vaginal discharge, and delay in the rate of reduction of the size of the uterus < 2 cm/day [10]. Upper, lower, and catheter-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs) were defined using standard published criteria as previously described [7]. Claret stream infection (bacteremia) was defined as growth of a potential pathogen in one or more than claret culture bottles. The composite outcome of postpartum infection was defined as having one or more of the following: postpartum endometritis, UTI or bloodstream infection.

Data analysis

This nowadays report is the primary assay of data collected in this prospective cohort study. Summary statistics were used to characterize the cohort. Demographic characteristics and outcomes were compared betwixt delirious/hypothermic participants and normothermic participants using Chi-squared analysis for categorical variables and student's t-test or Wilcoxon Ranksum for continuous variables. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically pregnant. Dissever multivariable logistic regression models were used to identify factors associated with development of fever/hypothermia, postpartum endometritis and the composite postpartum infection upshot. Predictor variables selected for potential inclusion in each model included published gamble factors for postpartum fever and infection such as age, parity, employment, district of residence, comorbidities, number of vaginal exams in labor, and reported duration of labor. Additional variables were included if on bivariate analysis they demonstrated a correlation with the outcome of interest with a P-value < 0.1. Backwards stepwise elimination was used to create the final model, and all variables with P-values< 0.05 in the final model were considered significant independent predictors of the upshot. Information from all participants enrolled into the study were included in the terminal analysis regardless of whether the subjects were retained or later withdrew. If patients withdrew their consent, no further sample or data drove was performed. All analyses were performed using Stata software (Version 12.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Enrollment and demographics

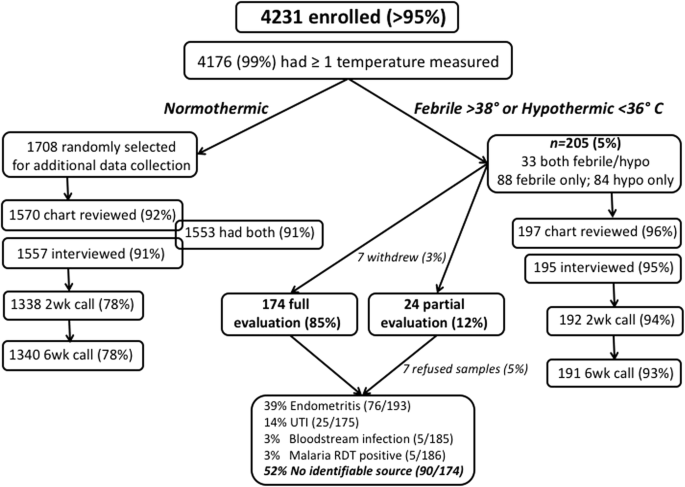

Of all eligible women presenting to MRRH for care during the study menstruation, over 99% (4235) were enrolled, four withdrew earlier data collection was performed, for a total enrollment of 4231. At least one temperature measurement was recorded for 4176 (99%) of participants, and two or more than measurements were recorded for 2917 (69%, Fig. 1). Among the 4176 participants with a temperature recording, fever/hypothermia was recorded at least once in 205 (5%). Of these, x (5%) were missing interview or nautical chart review and 14 (7%) were missing 2-week and 6-calendar week follow up data. Of 1708 normothermic participants randomly selected for additional data drove, 138 (8%) and 151 (nine%) were missing nautical chart review and interview data, respectively. Two- and six-week follow up data was missing in 368 (22%) and 370 (22%) respectively (Fig. 1). Of those who underwent chart review and interview, missing data ranged from 0 to 8% for individual variables.

Enrollment, retentivity, clinical and laboratory testing for women enrolled into a prospective cohort study of postpartum infection at Mbarara Regional Referral Infirmary, Uganda

Amid the 1913 febrile/hypothermic and randomly selected normothermic women, 1752 underwent interview and 1767 underwent chart review. The hateful historic period was 25.2 years (standard deviation (SD) 5.5 years), 214 (12%) were HIV-infected, 874 (51%) delivered by cesarean, and 662 (38%) were primiparous (Table ane). The mean historic period of febrile/hypothermic participants was significantly younger than normothermic participants (23.5 versus 25.4 years, SD 5.v years, P < 0.001). Delirious/hypothermic participants were also less probable to reside within Mbarara (32% versus 45%, P = 0.001) or to exist formally employed (41% versus 26%, P < 0.001). Febrile/hypothermic participants were more probable to be referred from some other wellness facility (24% versus 12%, P < 0.001) and more likely to be primiparous (55% versus 36%, P < 0.001) than normothermic participants. Cesarean delivery was too significantly more than common among febrile/hypothermic participants (81% versus 47%, P < 0.001). The proportion of HIV-infected did not differ between the two groups (12% each P = 0.86).

Evaluation of fever and hypothermia

Of 205 febrile or hypothermic participants, 174 (85%) completed concrete exam and symptom questionnaire, provided blood and urine cultures, and underwent malaria RDT. Another vii/205 (3%) withdrew from the report, and 24/205 (12%) underwent partial evaluation: 7/205 (iii%) refused sample collection and clinical evaluation but did not withdraw, 11/205 (five%) were missing urine civilization, 1/205 (0.5%) was missing claret cultures, iii/205 (1%) refused sample drove but underwent clinical examination and two/205 (1%) refused clinical exam and sample collection but completed the symptom questionnaire (Fig. 1).

In-hospital postpartum infection incidence

Overall, 84/4231 (2%) of participants met criteria for ane or more than in-infirmary postpartum infections. Endometritis was the most common, identified in 76/193 (39%) of women evaluated clinically. Of these 74 women with clinical endometritis and a recorded delivery style, 61 (82%) delivered by cesarean, for a postpartum endometritis incidence of 7% among all recorded 875 cesarean deliveries. Twenty-five of 175 (14%) participants with urinalysis and urine culture results met criteria for UTI. Bloodstream infection was diagnosed in 5/185 (3%) participants with blood culture results. Another 5/186 (3%) were malaria RDT-positive. A diagnosis of cesarean surgical site wound infection was recorded in the chart for v/205 (ii%) febrile or hypothermic participants. The remaining 90/174 (52%) participants fully evaluated did not have a documented source of fever afterwards our evaluation. The population attributable fraction (PAF) of postpartum infections due to cesarean delivery was 44%.

In-hospital complications

Development of whatever in-hospital complication (including surgical site infection, re-access to infirmary, re-functioning) was more common in febrile/hypothermic participants than normothermic participants (7% versus 1%, P < 0.001, Table ii). There was ane participant who died in the hospital from the febrile/hypothermic grouping versus none in the normothermic grouping (P = 0.11). More than febrile/hypothermic women than normothermic women had died by half dozen weeks postpartum (3 versus 0 deaths, P = 0.002). Birth and perinatal outcomes were also worse in the delirious/hypothermic grouping including a significantly higher number of stillbirths (ix% versus 3%, P < 0.001), and lower mean 5-min Apgar score (9.0 versus 9.vi, P < 0.001), and neonatal or infant death within 6 weeks of life (12% versus 5%, P < 0.001, Table ii).

Multivariable analysis of factors associated with postpartum outcomes

In multivariable logistic regression analysis, factors independently associated with postpartum fever/hypothermia included history of sexually transmitted infection (STI) during pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] four.0, 95% confidence interval [CI], i.7–9.6) and cesarean commitment (aOR two.9, 95% CI, i.viii–4.8, Table 3). Formal employment (aOR 0.v, 95% CI, 0.iii–0.8) and multiparity (aOR 0.5, 95% CI, 0.iii–0.7) were associated with reduced odds of postpartum fever/hypothermia. Factors independently associated with the composite in-infirmary postpartum infection outcome (including confirmed diagnosis of UTI, endometritis or bloodstream infection) were cesarean commitment (aOR iii.9, 95% CI, 1.5–x.3) and increasing number of days admitted to infirmary (aOR 1.two, 95% CI, 1.1–1.3). Attending antenatal care dispensary ≥four times was associated with reduced odds of postpartum infection (aOR 0.iv, 95% CI, 0.2–0.9, Table 4).

Factors independently associated with development of in-hospital clinically-confirmed diagnosis of postpartum endometritis, which was the most common consequence amongst the infections, were cesarean commitment (aOR ii.7, 95% CI, ane.2–vi.2) and increasing number of days admitted to hospital (aOR 1.ii, 95% CI, 1.1–1.three). Multiparity was associated with reduced odds of postpartum endometritis (aOR 0.5, 95% CI, 0.ii–1.0, Appendix ane).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort of women presenting to a Ugandan regional referral hospital, amidst those who developed postpartum fever/hypothermia, cesarean delivery was the strongest contained risk factor for developing endometritis or a composite postpartum infection outcome. Other hazard factors independently associated with postpartum infection included longer hospital stays and attending antenatal dispensary fewer than the four visits recommended by 2022 Ugandan national guidelines. Therefore, efforts should exist made to reduce the high proportion of cesarean deliveries, increase antenatal care attendance, reduce the number of days of admission and reduce the number of days of indwelling urethral catheters.

The incidence of postpartum fever or hypothermia in our accomplice was 5%, and a source of infection was confirmed in 48% of those with documented fever or hypothermia, for a 2% overall incidence of confirmed in-hospital postpartum infection. The overall fever and infection incidence we report here is low. However, the almost mutual infection amidst our participants was postpartum endometritis, and amid cesarean deliveries we report an incidence of (7%), over 3-fold greater than estimates from high-resource settings (ane.8–2.0%) [11,12,13]. Though infection incidence in Mbarara appears higher than European and North American estimates, comparing our findings to other low-resources settings is difficult. The reported incidence of postpartum endometritis in sub-Saharan Africa varies widely, likely due to differences in infection definition, surveillance, diagnosis, patient population and healthcare practices. Ane written report at Uganda's largest referral infirmary, where HIV prevalence is 21%, reported 73/478 (15%) patients undergoing emergency cesarean commitment adult postpartum endometritis [14], more than double the 7% incidence reported here. The lower incidence of postpartum endometritis nosotros report may reflect differences in exercise, antibody use, and infection command procedures within Republic of uganda. As well, the other Ugandan written report was published in 2011, at a time when fewer HIV-infected women were on antiretroviral therapy, which could take led to higher infection rates. Historically, HIV has been associated with increased risks of postpartum sepsis, including postpartum endometritis [fifteen]. Other studies from sub-Saharan Africa written report postpartum endometritis in 1–17% afterward cesarean commitment [16,17,xviii,19,20], and our report of 7% incidence falls inside this broad range. Though the incidence we report hither is relatively low, postpartum infection may get more common in sub-Saharan Africa as a result of increasing cesarean commitment rates coupled with rising incidence of nosocomial infections [vii].

Nosotros found UTIs in 14% and bloodstream infections in 3% of febrile/hypothermic participants. Comparisons of the incidence of UTI and bloodstream infections to other studies are difficult, every bit these infections are divers and reported inconsistently in the few other studies from sub-Saharan Africa [xiii, 14]. However, postpartum UTI incidence in some European studies is as low every bit 3% later on cesarean delivery and two% after vaginal commitment [21]. The difference in UTI incidence between our study and the other studies may exist attributable to the fact that laboratory diagnosis of UTIs in our written report was performed but for febrile and hypothermic participants, a group with a high likelihood of infection. It is also possible that cesarean commitment training and urinary catheter days may differ in other settings.

Report of sexually transmitted infection diagnosis during pregnancy, cesarean delivery, increasing number of hospital days, lack of formal employment and primiparity were independently associated with fever/hypothermia in our accomplice. Predictors of postpartum fever in low-resource settings are not very well described in the literature, except that prolonged second stage of labor is a risk factor for postpartum fever [ii]. Our study of postpartum fever associations with STIs and primiparity is non reported elsewhere in the literature, and claim further investigation.

Of note, birth and perinatal outcomes were overall worse in the fever/hypothermic grouping compared to the normothermic group. It is possible these differences reflect a pathological process nowadays before delivery which could have contributed to poor fetal and neonatal outcomes. This is an expanse of investigation that should be explored to meliorate understand maternal inflammatory and infectious contributors to stillbirth and early neonatal death and how to forestall postpartum infection.

Cesarean delivery was associated with the composite in-hospital postpartum infection outcome (including confirmed diagnosis of UTI, endometritis or bloodstream infection). In fact, in multivariable logistic regression models for each of the three outcomes (fever/hypothermia, endometritis, postpartum infection composite consequence), cesarean commitment was independently associated with each outcome with adjusted odds ratios of two.7–3.9. This finding is consistent with other reports that postpartum infection is three times more likely to occur after cesarean department than after vaginal commitment [22]. In add-on, the population attributable fraction of postpartum fever and postpartum infections due to cesarean commitment in our report was 44%. Our findings support previous research indicating that cesarean commitment is the most important take a chance factor for developing postpartum infection [iii, 6, 23]. Our results should reinforce efforts to reduce cesarean delivery rates to appropriate levels to avoid preventable, cesarean-associated infections. In improver, antibiotic prophylaxis, aseptic delivery, and postpartum care weather should continue to be emphasized as important factors mitigating infection chance. We also constitute that attending the recommended number of antenatal care visits (≥4 times during pregnancy at the time this study was conducted) was associated with reduced odds postpartum infection. Antenatal clinic interventions may help prevent postpartum infection through earlier detection and treatment of disease conditions, including sexually transmitted infections and UTI. Lastly, long infirmary stays are a known gamble factor for developing postpartum UTIs [23], and likely contribute to incident postpartum endometritis. Though prolonged hospitalization can result from fever or infection, information technology can too contribute to evolution of infection through increasing nosocomial transmission risk, prolonged exposure to invasive catheters and devices, and unhygienic conditions.

Strengths of our written report include the prospective study design, large sample size, most-complete enrollment of eligible women seeking care at MRRH during the written report period, and an in-depth clinical and microbiological evaluation of participants with suspected infection. Of note, at MRRH cesarean deliveries are performed under spinal anesthesia, and no cesarean or vaginal delivery participants had epidural anesthesia for labor analgesia. Epidural placement is i of the commonest causes of fever in labor and immediate postpartum period [24, 25], merely does not confound the findings in our study.

Limitations of our study include reliance on chart diagnosis of surgical site wound infection, which was inconsistently documented. Though the initial study design did not include wound infection every bit part of the composite postpartum infection outcome, cesarean surgical site infection is a known cause of postpartum fever [26] and may account for a high proportion of fevers and hypothermia in participants with no other confirmed infectious source after our evaluation. We abstracted chart diagnosis of cesarean section surgical site infections but did not perform clinical or microbiologic evaluation of these infections. Lack of confirmation of cesarean wound infections is a limitation of our written report since these are probable under-reported inpatient charts. In addition, due to resource constraints, we were unable to perform clinical or microbiological testing of normothermic participants and thus unable to determine the incidence of infection in the normothermic group. Nonetheless, we look that clinically significant in-hospital postpartum infections would include fever or hypothermia and therefore we believe we were unlikely to have missed significant infections in normothermic women. Prolonged rupture of membranes is a known risk gene for postpartum infection but was non straight measured in this study. Nosotros nerveless participant-reported duration of labor as one measurement of prolonged labor just we did non measure duration of membrane rupture directly. Lastly, at this regional referral hospital cesarean deliveries are common, accounting for 50% of all deliveries in this study. Though the cesarean delivery rate is high at MRRH, 50% may overestimate the true cesarean delivery charge per unit due to early on discharge and non-enrollment of some women delivering vaginally. We documented whether a woman was prescribed antibiotics on the same mean solar day as her cesarean section process, but we were unable to confirm whether these were given, nor decide the timing of the prescription relative to the procedure. Future research should address infections occurring after hospital discharge, incident in-hospital and mail-discharge surgical site infection, and the impact of rubber antibiotics on incident infection and development of antimicrobial resistance.

Conclusions

In our depression-resources setting, cesarean commitment is independently associated with gamble of incident in-hospital postpartum fever/hypothermia, endometritis and a composite postpartum infection outcome. Other contained risk factors for postpartum infection include longer hospital stays and attention antenatal clinic fewer than the recommended four visits. Efforts at reducing the loftier proportion cesarean deliveries, increasing antenatal intendance attendance, and reducing the number of days admitted and days of urethral indwelling catheter need to be optimized. With the loftier proportion of women with no identifiable source of infection, there is need for better bedside diagnostic means and antimicrobial evidence-based prescription.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal clinic

- CAUTI:

-

Catheter-associated urinary tract infection

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- MRRH:

-

Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RDT:

-

Rapid diagnostic exam

- SD:

-

Standard difference

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted infection

- TMP/SMX:

-

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole

- UGx:

-

Ugandan shillings

- UTI:

-

Urinary tract infection

References

-

Miller AE, Morgan C, Vyankandondera J. Causes of puerperal and neonatal sepsis in resource-constrained settings and advocacy for an integrated customs-based postnatal arroyo. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;123(1):ten–5.

-

Janni W, Schiessl B, Peschers U, Huber Due south, Strobl B, Hantschmann P, Uhlmann Northward, Dimpfl T, Rammel G, Kainer F. The prognostic impact of a prolonged 2nd stage of labor on maternal and fetal outcome. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81(three):214–21.

-

van Dillen J, Zwart J, Schutte J, van Roosmalen J. Maternal sepsis: epidemiology, etiology and outcome. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23(3):249–54.

-

Lapinsky SE. Obstetric infections. Crit Intendance Clin. 2013;29(three):509–20.

-

Ngonzi J, Tornes YF, Mukasa PK, Salongo Due west, Kabakyenga J, Sezalio G, Wouters K, Jacqueym Y, Van Geertruyden J-P. Puerperal sepsis, the leading cause of maternal deaths at a Tertiary University Teaching Hospital in Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):207.

-

Maharaj D. Puerperal pyrexia: a review. Function I. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(6):393–9.

-

Bebell LM, Ngonzi J, Bazira J, Fajardo Y, Boatin AA, Siedner MJ, Bassett IV, Nyehangane D, Nanjebe D, Jacquemyn Y, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant infections among postpartum women at a Ugandan referral hospital. PLoS One. 2017;12(four):e0175456.

-

Bebell LM, Ngonzi J, Siedner MJ, Muyindike WR, Bwana BM, Riley LE, Boum Y, Bangsberg DR, Bassett IV. HIV Infection and risk of postpartum infection, complications and mortality in rural Uganda. AIDS Care. 2018:1–11.

-

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational inquiry computer science support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(ii):377–81.

-

Dolea C, Stein C. Global burden of maternal sepsis in the year 2000, vol. 2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

-

Yokoe DS, Christiansen CL, Johnson R, Sands KE, Livingston J, Shtatland ES, Platt R. Epidemiology of and surveillance for postpartum infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(five):837.

-

Axelsson D, Blomberg M. Prevalence of postpartum infections: a population-based observational study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93(x):1065–8.

-

Ahnfeldt-Mollerup P, Petersen LK, Kragstrup J, Christensen RD, Sorensen B. Postpartum infections: occurrence, healthcare contacts and association with breastfeeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(12):1440–4.

-

Wandabwa JN, Doyle P, Longo-Mbenza B, Kiondo P, Khainza B, Othieno Due east, Maconichie N. Human immunodeficiency virus and AIDS and other important predictors of maternal bloodshed in Mulago Hospital Circuitous Kampala Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(one):1.

-

Calvert C, Ronsmans C. HIV and the adventure of directly obstetric complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Ane. 2013;8(10):e74848.

-

Moodliar Southward, Moodley J, Esterhuizen T. Complications associated with caesarean delivery in a setting with high HIV prevalence rates. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;131(two):138–45.

-

Bako B, Audu BM, Lawan ZM, Umar JB. Take chances factors and microbial isolates of puerperal sepsis at the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital, Maiduguri, Northward-eastern Nigeria. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285(four):913–7.

-

Mutihir JT, Utoo B. Postpartum maternal morbidity in Jos, north-central Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2011;14(1)

-

Mivumbi VN, Fiddling SE, Rulisa S, Greenberg JA. Prophylactic ampicillin versus cefazolin for the prevention of mail-cesarean infectious morbidity in Rwanda. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2014;124(3):244–7.

-

Khaskheli M-N, Baloch Due south, Sheeba A. Risk factors and complications of puerperal sepsis at a tertiary healthcare middle. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29(4):972.

-

Leth RA, Moller JK, Thomsen RW, Uldbjerg N, Norgaard M. Risk of selected postpartum infections later cesarean section compared with vaginal birth: a 5-year cohort written report of 32,468 women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(ix):976–83.

-

Kankuri E, Kurki T, Carlson P, Hiilesmaa Five. Incidence, treatment and outcome of peripartum sepsis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(eight):730–5.

-

Schwartz MA, Wang CC, Eckert LO, Critchlow CW. Hazard factors for urinary tract infection in the postpartum flow. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(3):547–53.

-

Segal Southward. Labor epidural analgesia and maternal fever. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(6):1467–75.

-

Herbst A, Wølner-Hanssen P, Ingemarsson I. Risk factors for fever in labor. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(five):790–four.

-

Collin SM, Baggaley RF, Pittrof R, Filippi V. Could a simple antenatal packet combining micronutritional supplementation with presumptive treatment of infection prevent maternal deaths in sub-Saharan Africa? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;seven:half-dozen.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all study participants, study staff, and BD (Becton, Dickinson, and Company, Belgium) for the generous donation of blood civilization bottles used in this written report, every bit well as the staff of Epicentre Mbarara Enquiry Eye, MGH Center for Global Health, Academy of Antwerp International Health Unit of measurement, Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital and Maternity Ward staff, and Mbarara University of Science and Technology for their partnership in this research.

Funding

LMB — Bacon supported by NIH Enquiry Training Grant # R25 TW009337 funded by the Fogarty International Center and the National Institute of Mental Wellness, NIH T32 Ruth 50. Kirschstein National Inquiry Service Laurels #5T32AI007433–22, KL2/Catalyst Medical Research Investigator Training award (an appointed KL2 honour) from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Scientific discipline Center (National Centre for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award KL2 TR001100) and the Charles H. Hood Foundation; travel supported by the MGH Center for Global Health. IVB — Harvard Academy Centre for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI060354), which is supported past the post-obit NIH Co-Funding and Participating Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, NIDDK, NIGMS, NIMHD, FIC, and OAR. MJS — NIH (K23 MH09916). DRB — Sullivan Family Foundation. BJW — National Institutes of Wellness (NIH K23 ES021471). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does non necessarily correspond the official views of Harvard Goad, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, or the National Institutes of Health. The funding bodies listed hither had no role in the design of the study, or drove, analysis, and estimation of information, or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of information and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the electric current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Writer information

Affiliations

Contributions

JN conceptualized the research idea, collected and analyzed information, drafted the manuscript and participated in disquisitional revisions. LMB conceptualized the research thought, nerveless and analyzed data, drafted the manuscript and participated in critical revisions. YF conceptualized the research idea and participated in critical revisions. AB conceptualized the research idea and participated in critical revisions. MJS participated in data analysis and critical manuscript revisions. IVB participated in data analysis and critical manuscript revisions. YJ participated in data assay and critical manuscript revisions. JPVg participated in data analysis and critical manuscript revisions. JK conceptualized the research idea and participated in disquisitional manuscript revisions. BJW conceptualized the research idea, participated in data assay and critical manuscript revisions. DRB conceptualized the inquiry thought and participated in disquisitional manuscript revisions. LER conceptualized the inquiry idea and participated in critical revisions. We ostend that all authors have read and approved the concluding version of the manuscript.

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Ideals approval and consent to participate

Upstanding review and clearance was obtained from Mbarara University Research Ethical Commission (08/10–14), Uganda National Council and Technology (HS/1729) and Partners Healthcare (2014P002725/MGH). All participants gave informed written consent to participate in the written report.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

We confirm that author Yves Jacqueymn serves on the Editorial Lath of BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth as Associate Editor. We likewise confirm that all other authors have no competing interests to declare.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/), which permits unrestricted utilise, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you requite appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this commodity

Ngonzi, J., Bebell, Fifty.Yard., Fajardo, Y. et al. Incidence of postpartum infection, outcomes and associated gamble factors at Mbarara regional referral hospital in Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 270 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1891-1

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1891-1

Keywords

- Incidence

- Risk factors

- Postpartum

- Uganda

- Resource limited

- Pregnant women

- Labor

- Africa

- Infection

- Puerperal sepsis

manningbutervirty.blogspot.com

Source: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-018-1891-1

Post a Comment for "Which Intrapartal Factors Can Contribute to a Postpartum Infection? Select All That Apply."